'HEAR' WORD

In order for our brain to attach meaning to a printed word, it has to 'hear' it first

How can our brain 'hear' a word if we are not reading out loud?

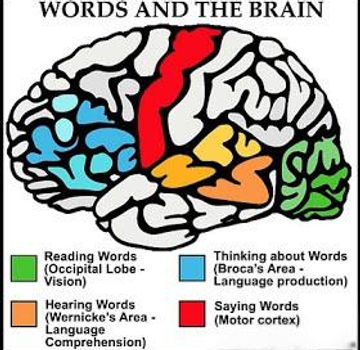

The Wernicke-Geschwind model indicates that the primary visual cortex is what mediates the visual information our brain receives when we see written words (Pinel & Edwards, 2008). The visual word form area (VWFA) of the left posterior temporal cortex is activated by seeing strings of letters or words (Pinel & Edwards, 2008). Translating the image of a word into an auditory code is the work of the left angular gyrus, which then sends the information to Wernicke’s area, located posterior to the primary auditory cortex in the left temporal lobe, where it “mediates the comprehension of spoken language” (Pinel & Edwards, 2008, p. 208).

What this means is that our brains have to ‘hear’ a word before we understand it. This is because we are hard-wired for spoken language but we have to be taught written language. We learn spoken language implicitly and without instruction, but in order to understand written language, our brain relies on a network of processes that translate the visual information into what our brain is hard-wired to do--understand spoken language (Seidenberg, 2017).

Figure 3 shows the different areas of the brain that are activated when performing various aspects of language and communication

Retrieved from: https://images.slideplayer.com/14/4281018/slides/slide_14.jpg

Geake (2007) states that literacy “requires decoding and encoding symbol systems which simultaneously correspond with the brain’s auditory, visual and semantic networks (p. 133). Castles et al. (2018) refers to this process as “cracking the alphabetic code” (p. 8). This means that students need to associate meaning with the letters of the alphabet which are no more than “arbitrary visual symbols--patterns of lines, curves, and dots” (Castles et al., 2018, p. 8). They maintain that this skill is a “critical starting point for learning to read” (p. 11) and they further attest that “phonics is crucial because it gives children the skills to translate orthography into phonology and thereby to access knowledge about meaning” (p. 15). This is because children already have a rich oral vocabulary even before they learn to read (Castles et al., 2018). Bilingual students entering school have a particular challenge learning to read in a second language because their oral skills are based on their first language which puts them behind their monolingual classmates (Paez et al., 2010). Seidenberg (2017) refers to reading and speech as “codependents in a long term relationship” (p. 106) that changes over time; one in which speech is initially dominant but eventually, reading catches up, to the point where it surpasses oral language and overtakes it as the means to learning specialized knowledge.

In the brain, the VWFA (Visual Word Form Area) mentioned above, is implicated in integrating sounds (phonology) and print (orthography) but as yet, it is still not conclusive how it does this (Shaywitz & Shaywitz, 2008). Castles et al. (2018) refer to this association between letter knowledge, phonemic awareness and decoding skills as “intimate and reciprocal” (p. 11), of which the VWFA is essential.

Figure 4 highlights the main areas of the brain involved in language

A student gains access to the meaning of a word by translating its spelling into sound through a dual pathway of either direct print to meaning or decoding the sounds and blending them together to form a word (Castles et. al, 2018). The goal is to gain lexical quality, which is how precise and flexible the stored mental representation is to the word. The higher the lexical quality, which is gained through frequent exposure, the more the brain can use the direct from print-to-meaning route and the easier it is to access its meaning from memory through the hippocampus (Castles et al., 2018). Since reading places great demands on attention and memory, if a student has greater access to the direct pathway, it can free up cognitive resources that can then go to higher level language processes like overall reading comprehension. Further, oral vocabulary is the foundation for reading comprehension in the sense that once the brain decodes and recognizes the sound of a word, it can draw meaning from a student’s oral vocabulary memory, an insight that Castles et al. (2018) reveals that a “low level’ process underpins[s]” and is an “essential foundation for the high-level ones” (p. 21). Once children can decode words, it allows them access to pronunciation which in turn, reveals meaning because it gives the brain access to stored oral language meanings (Castles et al., 2018).

What kind of vocabulary strategy can take advantage of the brain's need to 'hear' a word in order to understand it?

The ‘Say it Outloud’ strategy does just that. Whenever I design a reading quiz, one type of word I try to select is one that students may have heard before but may not recognize in print. An example would be the word "catastrophe". This word is one that is used in speech often but studens may not recognize and have to decode, paying particular attention to the 'ph' combination making the /f/ sound.

In the example below from a reading quiz I designed, the selected word is “dawdled”. I chose this word because it is not a frequently used word in text, but it may be one students have heard in speech, particularly from a grandparent or parent. In the passage below, the word "dawdled" is highlighted.

Retrieved from: https://archive.org/stream/grade9achieveme1990albe_0/grade9achieveme1990albe_0_djvu.txt

The word is an ideal choice for the quiz because the meaning is not likely to be derived from the context of the sentence, nor to the meaning of word parts.

Reading Quiz question created by Shelly Cloke, 2013

**It should be noted that these strategies would not work for every student. English Language Learners, students with dyslexia or language delays or students who struggle to decode words would be less effective for these students.